Rust Security & Auditing Guide by Sherlock: 2026

Where Rust security actually breaks in 2026: unsafe contracts, FFI boundaries, async deadlocks, and supply chain gaps. Technical audit patterns with Miri, sanitizers, and fuzzing.

Executive summary: Rust raises the security floor, but the failures that matter in 2026 come from broken assumptions rather than memory corruption.

- Unsafe Rust introduces contracts around alignment, aliasing, and lifetimes that must be proven and defended as code evolves

- Most exploitable behavior emerges at boundaries: deserialization, async concurrency, nondeterminism, and resource exhaustion under adversarial input

- Real risk often enters at build and release time, where feature flags, target-specific dependencies, and transitive unsafe mean the binary in production is not the code that was reviewed

Rust Security & Auditing Guide by Sherlock: 2026

Rust’s biggest security promise is real: in safe code, you avoid entire families of memory bugs that still dominate incident writeups in C and C++. The trap is thinking that “memory safe” means “secure.” In 2026, the Rust failures that matter most show up in four places: unsafe contracts that silently drift into undefined behavior, boundary code that accepts attacker-shaped inputs, concurrency paths that deadlock or starve under load, and supply-chain/packaging gaps where the code you audited is not the code you shipped.

This guide is technical on purpose. It’s written as a set of patterns that show up repeatedly in real audits and postmortems, with concrete code examples and the specific tools that surface each class of issue. Wherever I reference a tool’s behavior or a safety rule, I cite the primary docs.

Start where Rust actually leaks risk: Unsafe contracts, not “unsafe blocks”

Most audit writeups talk about “unsafe code” as a blob. That misses the point. Unsafe Rust is a promise you’re making to the compiler and to future maintainers: “these invariants hold.” Your audit job is to prove those invariants, then reduce the chance they get broken later.

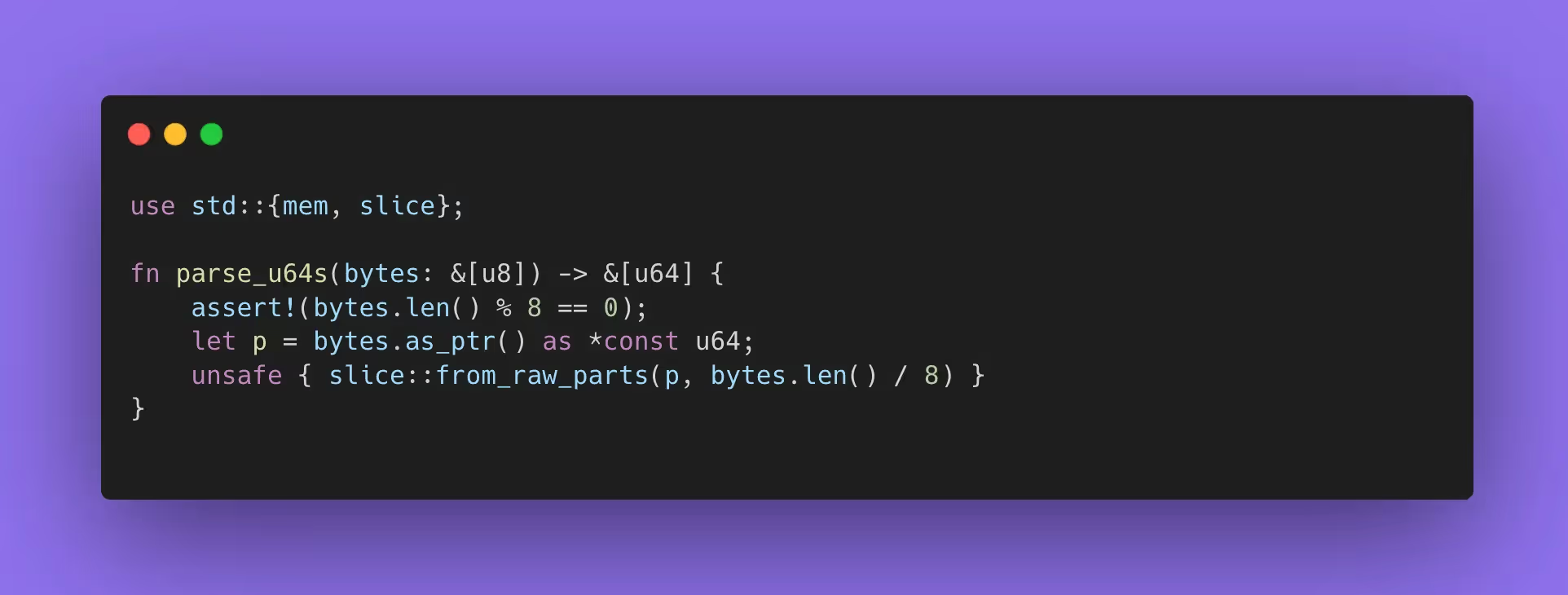

Take std::slice::from_raw_parts. Its safety contract is explicit: pointer must be non-null, properly aligned, valid for len * size_of::<T>() bytes, and must uphold aliasing rules the optimizer assumes. Violating any of that is undefined behavior.

Here’s a compact example that looks fine at a glance and will pass normal tests, then bite you when the compiler or platform layout changes:

This has an alignment landmine. bytes.as_ptr() is aligned for u8, which has alignment 1. Casting to *const u64 does not magically make it aligned to 8. On some platforms it “works,” until it doesn’t. Tools like Miri catch this because they model alignment requirements and report UB instead of letting it slip. You’ll see errors of exactly this shape in the wild: “encountered an unaligned reference (required 8 byte alignment but found 1).”

A secure rewrite depends on what you’re trying to do. If you want a view, you can copy into aligned storage or use safe parsing (often faster than you think if you batch). For audit purposes, the important part is to document the contract, then encode it so future refactors cannot silently violate it. Two approaches that survive refactors well are: (1) keep the data typed as [u64] from the source of truth (you allocate aligned storage once), or (2) parse via u64::from_le_bytes in a loop, which is branchless on many targets and removes the alignment/aliasing contract entirely.

The key audit move is to treat every unsafe conversion as a “contract boundary.” You’re checking alignment, validity, provenance/aliasing, and lifetime. If you want a research-level framing of what those safety tags look like in practice, there’s active work on annotating unsafe APIs like slice::from_raw_parts with the exact properties they require. T

Miri: the UB flashlight that turns “seems fine” into a failing test

Miri is a Rust interpreter that detects undefined behavior by enforcing the language’s rules at runtime, which is exactly what you need when unsafe code is relying on an assumption you can’t see in normal tests.

A useful way to integrate Miri into auditing is to add small, intentionally “mean” tests that exercise unsafe paths with boundary values: zero lengths, odd alignments, aliasing-like usage, and edge-case lifetimes. When a codebase has a handful of unsafe hotspots, you get disproportionate value by making those hotspots Miri-clean. This is one of the fastest ways to turn “we think it’s safe” into “we have evidence.”

Sanitizers: the missing link when Rust meets C, C++, and the OS

Miri is great for Rust semantics. Sanitizers are great for the memory model of the whole process: FFI buffers, allocator misuse, use-after-free, out-of-bounds access, leaks, and thread races that arise in mixed-language systems.

Rust’s compiler toolchain supports multiple sanitizers. The rustc dev guide documents the feature set and what each sanitizer detects, and the unstable book shows how the flags are enabled.

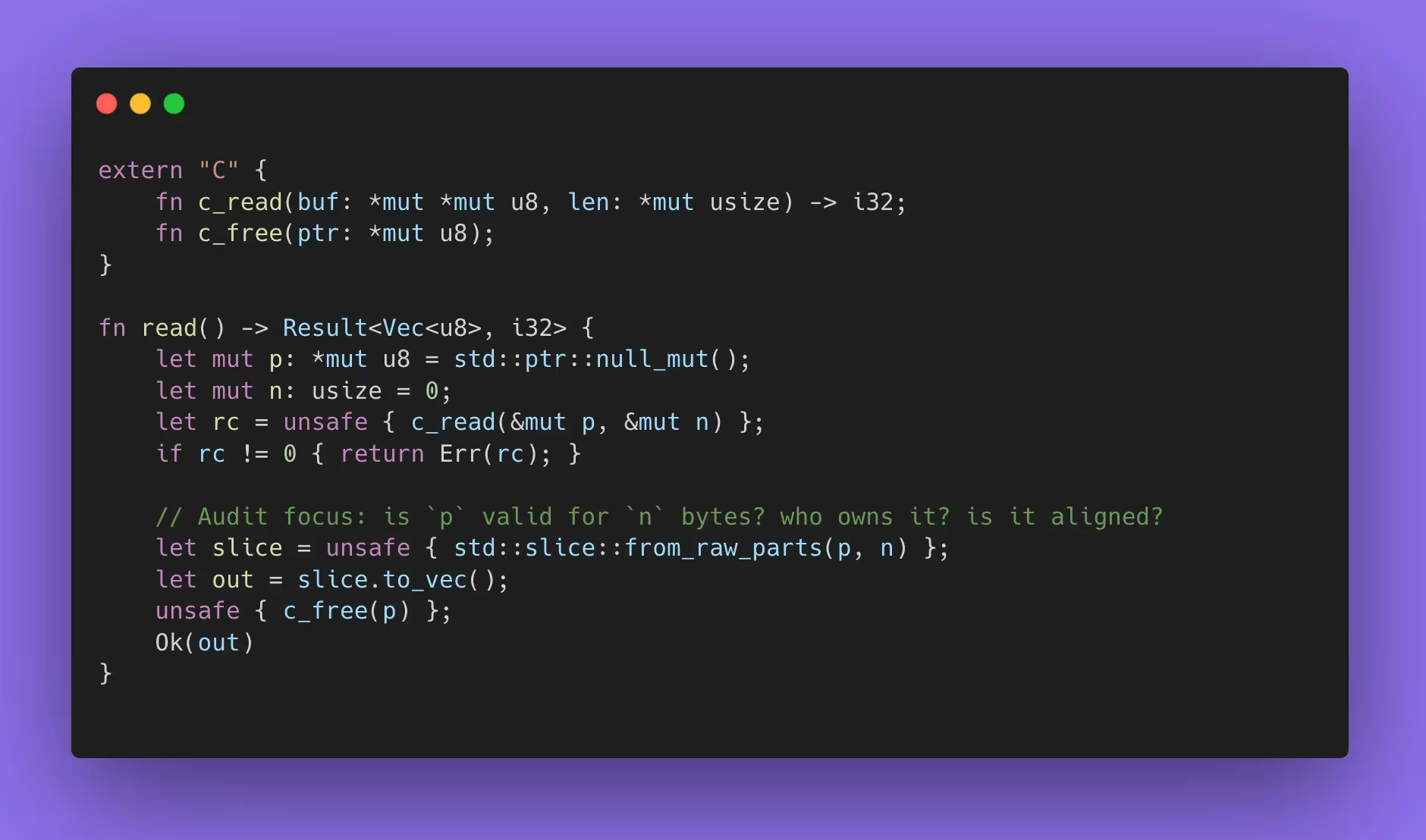

Here’s the practical audit angle: if your Rust service calls into C (or exposes a C ABI), you can have perfectly safe Rust wrappers around an unsafe C core that still double-frees or writes out of bounds. A sanitizer build turns those into crashes you can reproduce.

A typical “audit target” here is an FFI wrapper that returns a Vec<u8> from a C allocation:

This is common. The bug shows up when c_read sometimes returns a pointer you must free with a different function, or returns a pointer to static memory for a special case, or returns len that exceeds the allocation on certain paths. Sanitizers and fuzzing together are how you make those “rare C paths” show up during review instead of during an outage.

Fuzzing in Rust: focus on “panic surfaces,” then move to invariants

Rust fuzzing advice often starts with “fuzz your parsers.” That’s right, but incomplete. In Rust, fuzzing also finds security issues by triggering panics, integer edge cases, and pathological allocations that translate into denial-of-service.

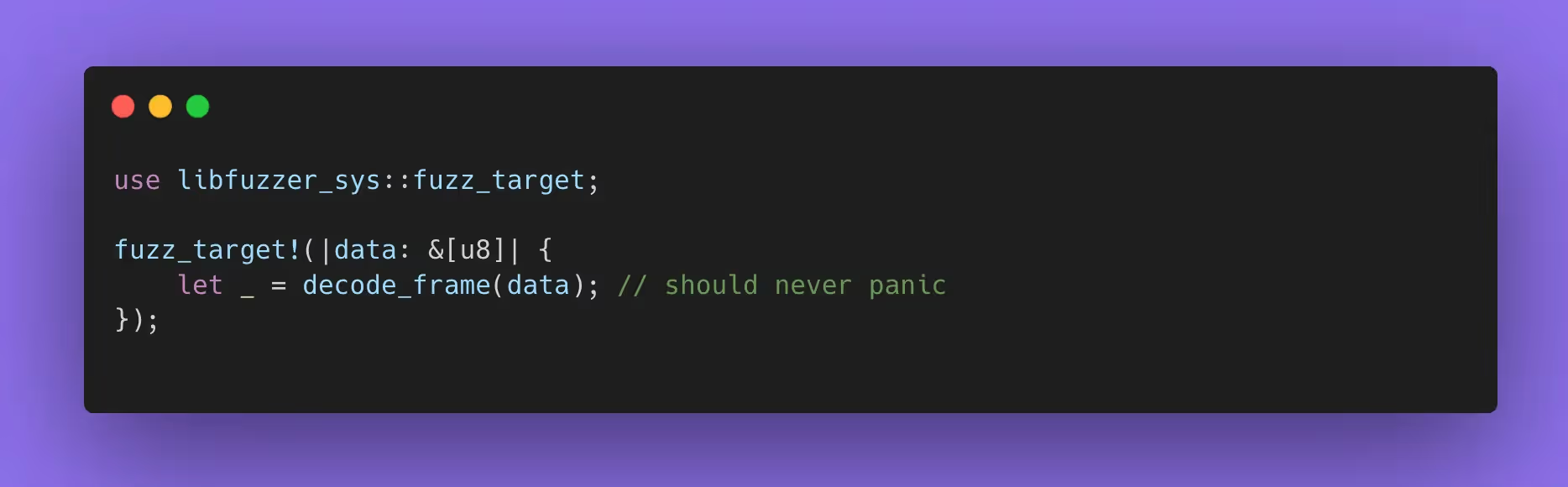

cargo-fuzz is the standard workflow, and it drives libFuzzer under the hood. The Rust Fuzz Book tutorial shows the intent clearly: generate inputs until you find a panic or crash.

A sharp 2026 audit pattern is to define fuzz targets around every boundary where attacker input becomes structured data: request deserialization, signature parsing, custom framing, compression, and file formats. The target is the smallest function that “turns bytes into meaning.” That makes crashes actionable and keeps the corpus small.

Example fuzz target for a custom message frame:

If you write decode_frame so it returns Result<Frame, Error> and never panics, fuzzing becomes a “panic detector” for regressions. That’s valuable even when the bug is “just a crash,” because remote crashes are frequently security-relevant for networked services.

Once panics are under control, move fuzzing up one layer: invariants. For instance, decode then re-encode should round-trip, or two different decoding routes should agree, or “validate then execute” should not accept a message that “execute” rejects later. Those are the bugs that become bypasses.

Concurrency bugs: safe Rust prevents data races, still leaves deadlocks and starvation

A 2026 Rust audit that ignores concurrency is leaving money on the table. The class of failure is subtle: nothing is “unsafe,” everything compiles, load tests pass, then production hits a cancellation storm or a slow downstream dependency and the system wedges.

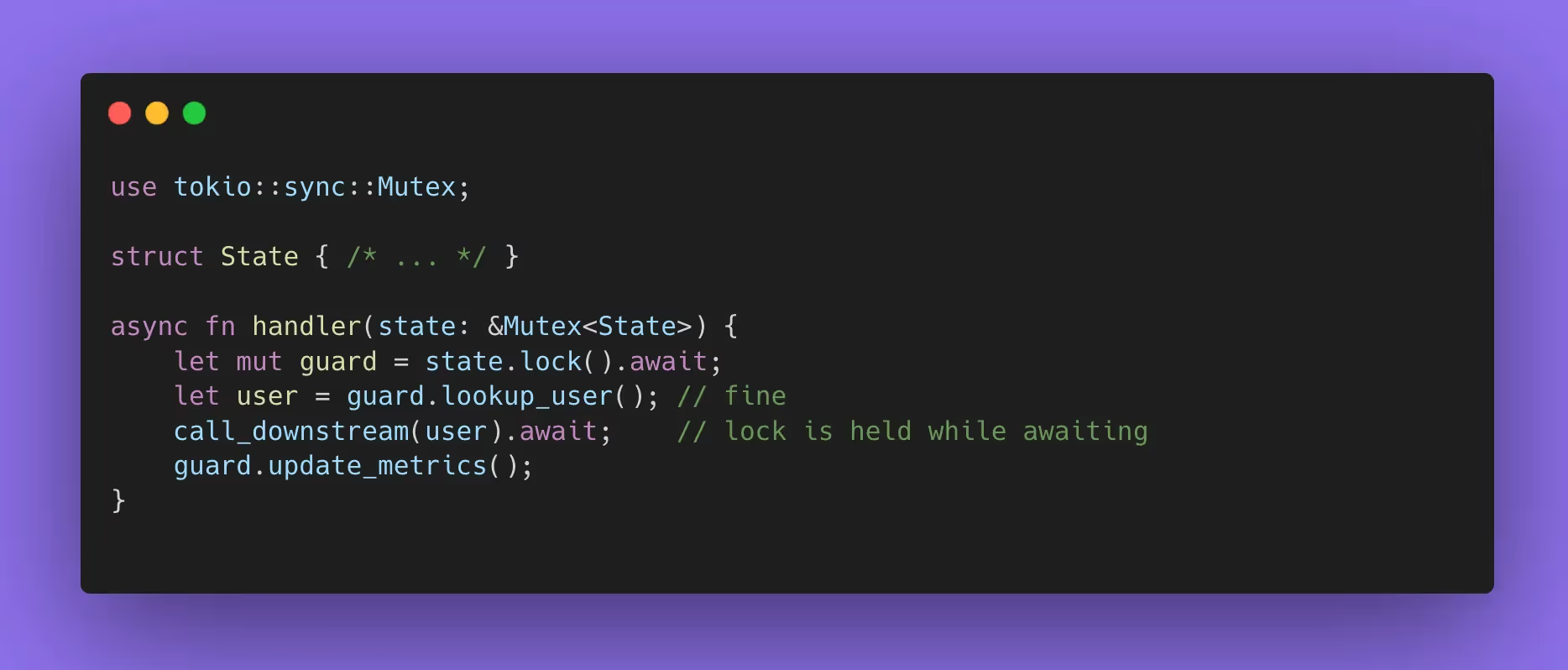

The canonical smell is holding a lock across an .await:

The exploit path is not “memory corruption.” It’s resource exhaustion: an attacker or noisy neighbor forces slow downstream calls and you serialize the entire service behind a single lock. In audits, you want to see lock scope end before await, or redesign with message passing, sharded state, or RwLock patterns that reduce contention.

A second smell is unbounded queues and tokio::spawn on attacker-controlled fanout. Rust makes it easy to create a million tasks. If each task holds memory and sits waiting, you have a clean DoS. Audits look for explicit backpressure, bounded channels, and timeouts around external calls.

Serialization and input ambiguity: serde is a footgun if you let it be permissive

Rust’s type system shines when you constrain inputs. Many teams undercut that by letting serde accept multiple representations or fill in defaults that change meaning.

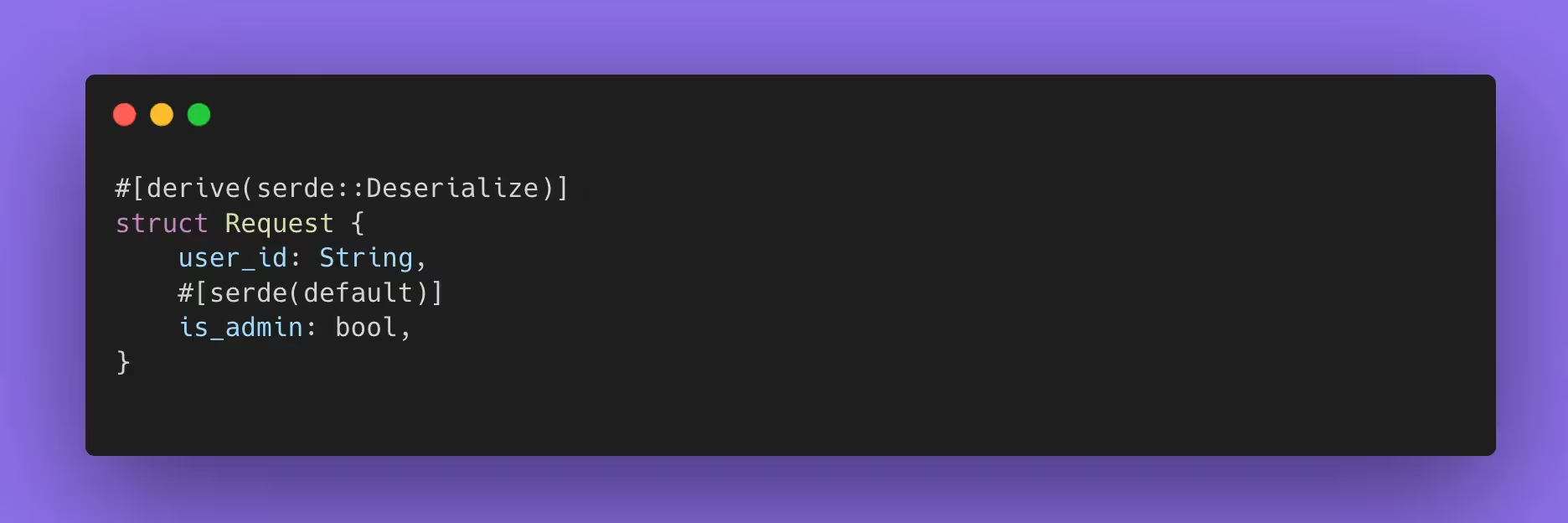

A classic bypass pattern is “missing field means default means privileged.” It looks like convenience:

If any upstream layer can omit is_admin, the default becomes security-significant. The fix is almost always to model intent: represent optional fields as Option<T> and validate explicitly, or use “deny unknown fields” so you fail closed when someone sends surprising input.

Audits also scrutinize numeric types. JSON and many wire formats do not faithfully represent 64-bit integers across ecosystems. If a signature covers the serialized form, you can get “same semantic value, different bytes” problems that become replay or bypass paths. The audit move is to choose canonical encoding, then enforce it at the boundary.

Supply chain and release posture: audit the shipped artifact, not the repo

By 2026, most Rust orgs scan dependencies in CI. Fewer scan what’s deployed. That gap matters, because “the repo” and “the artifact” drift due to feature flags, build scripts, platform-specific deps, and the reality that prod sometimes runs a build you did not expect.

Cargo-auditable solves a big slice of that: it embeds dependency tree metadata into a dedicated section of the compiled executable, so you can later identify the exact crate versions used in the binary. On top of that, cargo-audit has support for auditing a binary when it was built with auditable metadata, making the check accurate without external bookkeeping.

This is a concrete “2026-grade” recommendation: treat the artifact as the source of truth for vulnerability scanning. If you want SBOM correctness at scale, this is one of the cleaner ways to get it in Rust-centric stacks.

On the policy side, cargo-deny is widely used because it covers more than advisories. It can gate multiple versions of the same crate, disallow certain sources, and enforce license policy. The audit use case is straightforward: it turns “we should keep our dependency graph sane” into a build rule that fails when the graph grows warts.

Unsafe inheritance also belongs in supply-chain review. cargo-geiger gives you an attention map: where unsafe code appears across your full dependency graph. It does not mean “unsafe equals bad.” It means “this crate’s safety story is a contract, and we should know where those contracts live.”

Publishing risk: crates.io Trusted Publishing as a security control, not a convenience feature

When you ship internal libraries or publish open-source crates that other systems depend on, your release pipeline becomes a security boundary. A compromised publish token is an attacker’s dream.

crates.io’s Trusted Publishing uses OpenID Connect to issue short-lived tokens to CI workflows, so you avoid long-lived secrets sitting in a repo or CI settings. The Rust project has called this out in crates.io development updates, including setup guidance and the “first publish manually, then enable Trusted Publishing” workflow.

An audit angle that teams often miss: if you adopt Trusted Publishing, you also need to audit the GitHub Actions workflow permissions, branch protection, and tag strategy, because those become the real gate on release. OIDC reduces token theft risk; it does not eliminate the risk of “someone can run a publish job from an unexpected context.”

Bonus: Rust security in Web3 specific systems

Rust underpins much of Web3’s most sensitive infrastructure in 2026: execution clients, rollup nodes, provers, bridges, indexers, relayers, and off-chain workers that directly influence on-chain state. The dominant security risk here is not memory safety, but state divergence under adversarial conditions. A Rust binary that is “correct” in isolation can still violate consensus assumptions once replay, re-execution, partial trust, and economic incentives enter the picture. Auditing Web3 Rust code means proving that state transitions are deterministic, canonical, and invariant-preserving across machines, versions, and time, while resisting malformed inputs that are deliberately shaped to hit edge behavior rather than trigger obvious panics.

Determinism failures that cause consensus and proof breaks

A recurring real-world issue is nondeterminism leaking into consensus-critical logic through standard Rust constructs. HashMap and HashSet iteration order, locale- or platform-dependent parsing, implicit reliance on wall-clock time, and non-canonical serialization all show up in audits of rollups and off-chain executors.

These bugs are subtle because they do not cause crashes; they cause disagreement. Two nodes processing the same block data derive different commitments, proofs, or state roots, leading to verifier failure or fork conditions that are extremely costly to diagnose after the fact. Audits therefore trace every value that feeds into hashing, signing, proving, or state commitment and require explicit canonicalization: ordered collections, fixed serialization formats, deterministic math, and isolation from any ambient system state. In Web3 contexts, “probably deterministic” is functionally insecure.

Unsafe performance code in cryptography, provers, and zero-copy paths

The second major failure class lives in intentional unsafe code written for throughput. Rust-based provers, signature pipelines, and execution runtimes frequently rely on unsafe zero-copy deserialization, custom memory layouts, or unchecked arithmetic to meet performance targets. These blocks often assume well-formed inputs produced by the system itself. An attacker’s leverage comes from violating one invariant while still passing upstream validation, causing undefined behavior, silent miscomputation, or verifier divergence rather than a clean panic.

In Web3 audits, these unsafe regions receive deeper scrutiny than typical application code: reviewers enumerate every assumed invariant, verify enforcement at all external boundaries and upgrade paths, and apply targeted fuzzing and Miri execution against byte-level inputs that exercise alignment, length, and aliasing assumptions. When unsafe Rust fails in Web3 systems, the damage is rarely a crash; it is an incorrect state that propagates economically and is expensive or impossible to unwind.

Putting it together: what a serious Rust audit looks like in 2026

A good Rust audit reads like a proof and a set of experiments.

The proof is about invariants: permission boundaries, state transitions, and unsafe contracts. The experiments are tool-driven: Miri on unsafe hotspots, sanitizer builds for mixed-language paths, fuzz targets for each boundary decoder, and artifact-level dependency verification.

If you do one thing differently after reading this, make it this: write down the contract for each unsafe region in plain language, then add a small test that fails when the contract breaks. Pair that with fuzzing at the byte-to-structure boundary. Those two moves catch a large fraction of Rust security failures that slip past normal review.

If you’re building Web3 infrastructure in Rust and want confidence that your system holds up under adversarial conditions, Sherlock provides Rust security audits and architecture reviews focused on unsafe contracts, determinism, and real-world failure modes across rollups, provers, bridges, and off-chain systems. Contact Sherlock today.

FAQ: Common Security Questions Regarding Rust Security & Auditing

1. If Rust prevents memory bugs, why do serious vulnerabilities still happen?

Because most real incidents are caused by incorrect assumptions, not buffer overflows. Authorization logic, state invariants, serialization boundaries, and resource exhaustion are all fully possible in safe Rust. Memory safety removes a class of bugs; it does not validate intent or system-level behavior.

2. How much unsafe is acceptable in a production Rust system?

There is no universal number. What matters is whether every unsafe region has a clearly stated contract and whether that contract is enforced at all call sites. A small amount of undocumented unsafe code is riskier than a larger amount that is narrowly scoped, well-tested, and audited with tools like Miri.

3. Why do Rust audits focus so heavily on panics and crashes?

In networked systems, a panic is often a remote denial-of-service. In async systems, a panic inside a task can also leave shared state inconsistent. Audits treat “this panics on bad input” as a security signal, not just a reliability concern.

4. When should Miri be used instead of sanitizers?

Miri is best for catching undefined behavior in Rust semantics: alignment, aliasing, provenance, and lifetime violations. Sanitizers are better for mixed-language systems, allocator misuse, and low-level memory errors. In audits, they complement each other rather than compete.

5. Why is determinism such a big deal in Web3 Rust systems?

Because nondeterminism doesn’t usually cause crashes; it causes disagreement. If two nodes derive different state from the same inputs, you get verifier failure, proof rejection, or consensus splits. These failures are subtle, expensive, and often discovered only after economic damage has occurred.

6. Is fuzzing still useful if the code already has strong typing?

Yes. Strong typing does not prevent panics, pathological allocations, or invariant violations across function boundaries. Fuzzing is one of the most reliable ways to discover where “this should never happen” assumptions break under adversarial input.

7. Why audit the compiled artifact instead of just the repository?

Because production binaries differ from source trees due to feature flags, platform-specific dependencies, build scripts, and CI configuration. Auditing only the repo assumes the build process is perfect. Artifact-level auditing verifies what actually runs.

8. What is the single highest-leverage improvement most Rust teams can make?

Document unsafe contracts in plain language and write tests that fail when those contracts are violated. Pair that with fuzzing at byte-to-structure boundaries. Those two steps catch a large share of real-world Rust security issues before they ship.