Cross-Chain Security in 2026: Threat Models, Trust Assumptions, and Failure Modes

Practical guide to Web3 cross-chain security: threat models, trust assumptions, and failure modes for builders and auditors working with bridges and messaging systems.

Executive Summary: Cross-chain exploits in 2026 continue to follow predictable patterns: trust assumptions coded as guarantees, authentication failures at message boundaries, and systems that grant full authority through a single execution path.

- Most incidents trace to one violated assumption (finality mismatch, key compromise, replay) cascading because other layers assumed the first layer was guaranteed

- Fast bridging and composability have elevated economic attacks (MEV, timing manipulation) and systemic risk (bridged assets as DeFi primitives) to the same threat level as traditional forgery

- Monitoring, incident response, and explicit trust modeling are now core security requirements, not operational add-ons

Cross-Chain Security in 2026: Threat Models, Trust Assumptions, and Failure Modes

Why cross-chain security feels different than “regular” smart contract security

From where we sit at Sherlock, cross-chain work has one repeating theme: teams underestimate how much authority they are importing. A bridge or messaging layer rarely “moves tokens.” It moves a claim that some event happened elsewhere, and it asks the destination chain to treat that claim as real.

That is why we frame cross-chain systems as security adapters between two consensus domains: they translate finality, membership, and authorization from one chain into another chain’s execution environment.

Once you see that, the right opening question stops being “which bridge is safest?” The question becomes: what assumptions does this adapter rely on, and what breaks when any one of them fails?

This guide is built for builders and reviewers. It’s meant to help you write and audit cross-chain code that survives real adversarial conditions, under real market pressure, in a year where fast bridging and rollup-to-rollup messaging are now normal.

The core abstraction: how a message becomes authority

Every cross-chain design has to answer one thing: why does the destination chain believe a message?

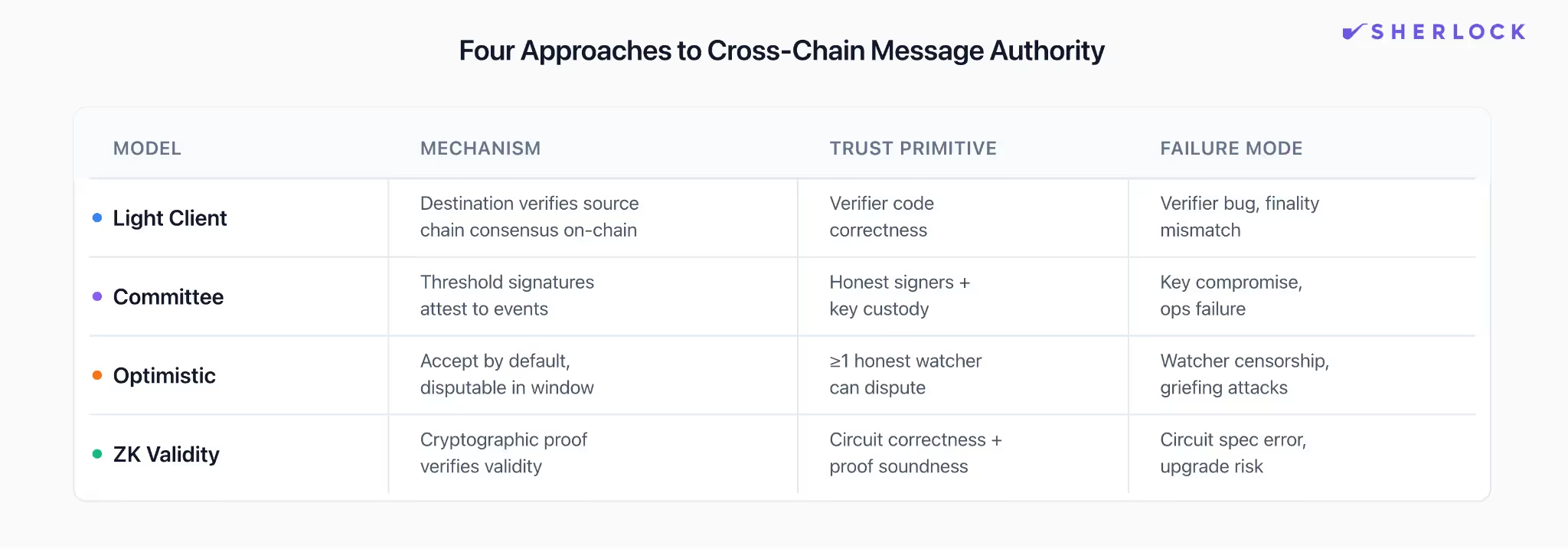

We group the answers into four families because they map cleanly to real trust assumptions and real failure classes.

Light-client verified messaging. The destination chain verifies the source chain’s consensus or finality rules via a light client (or an equivalent verifier) and accepts messages backed by proofs anchored to the source chain. This is the “verify the other chain’s state transitions” lineage most people associate with IBC. The promise is straightforward: belief comes from verification. The sharp edges also show up in predictable places: finality mismatches, verifier bugs, censorship-driven liveness loss, and misbehavior handling paths like freezes and recoveries.

Committee or external attestation. Here, belief comes from a threshold of signers: a multisig, MPC set, guardian quorum, oracle group, or validator committee. The design can be simple and fast, but the assumption is blunt: enough signers stay honest and uncompromised, and operations hold up under pressure.

Optimistic verification. In this family, a claim is accepted by default, and anyone can dispute it within a window, usually with bonds and an adjudication path. The assumption is subtler than it looks: at least one honest watcher is awake, funded, and able to get a dispute included on-chain during the window. In 2026, the important twist is that delay and griefing can be as damaging as direct forgery; systems can be dragged into “safe but unusable” states at a cost the attacker is happy to pay.

ZK validity bridges. Here, belief comes from a succinct validity proof: a prover attests to a source-chain statement, and the destination verifies the proof. This can shrink trust in intermediaries, but the assumption shifts into specification: the circuit must prove the right statement, and upgrades must be governed safely.

These families are less about marketing categories and more about what you’re betting on: code that verifies consensus, humans and keys, watcher economics, or proof systems and circuit specs.

Threat modeling that matches reality: three layers, three kinds of failure

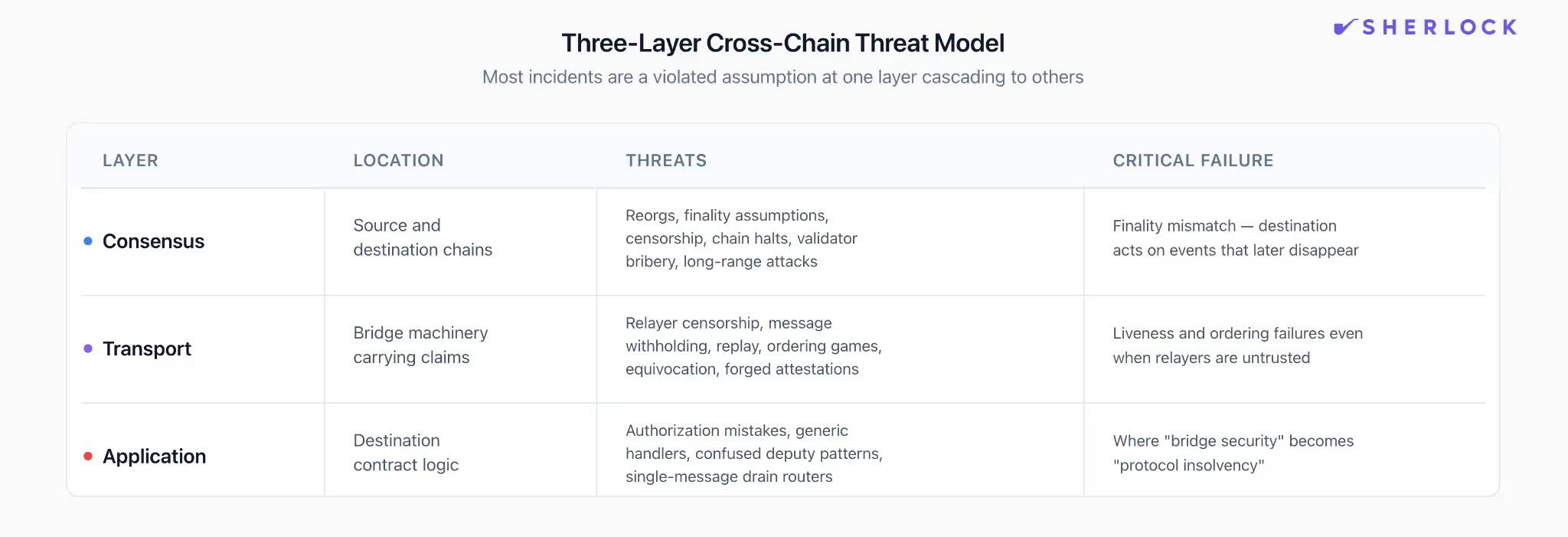

We’ve found that cross-chain reviews go off the rails when everything is treated as “the bridge.” A cleaner model separates the system into three layers that fail in different ways: consensus, transport, and application.

Consensus layer threats live on the source chain and destination chain: reorgs, finality assumptions, censorship, chain halts, validator bribery, long-range quirks depending on consensus. The cross-chain version that bites teams is finality mismatch: “final” on chain A is weaker than what your destination-side logic assumes, so you act on events that later disappear.

Transport layer threats live in the machinery that carries the claim: relayer censorship, message withholding, replay, ordering games, equivocation, forged attestations, proof substitution. Even designs that treat relayers as untrusted still face a liveness and ordering surface. IBC’s channel and packet semantics are a strong reference for why transport is modeled as a state machine rather than a single call.

Application layer threats live in what your destination contract does once it receives a message: authorization mistakes, generic handlers that can call arbitrary targets, confused-deputy patterns, and “one message drains everything” routers. This layer is where “bridge security” turns into “protocol insolvency.”

If you hold this three-layer model in your head, cross-chain incidents become legible: most are a violated assumption at one layer that cascades because the other layers were coded as if the assumption was guaranteed.

Failure modes that keep repeating

1) The destination accepts a message it should never accept

This shows up as signature verification bugs, bad domain separation, wrong endpoint configuration, or a verifier that can be tricked. In practice, it usually reads as “forged message, real money.”

The actionable takeaway is that “message accepted” is the moment your protocol grants authority. Your code should treat that moment as a high-value boundary, with clear invariants and a narrow surface.

2) Keys or signing operations fail under adversarial pressure

Committee designs can work, but we’ve watched too many teams treat signer ops as a background detail. Real attackers go after the shortest path to authority, and keys are often shorter than consensus. That is why the threat model has to include human processes, custody, and recovery rituals, not just Solidity.

3) Replay and ordering gaps become an extraction path

Even when authentication is solid, ordering assumptions silently leak into app logic. A cross-chain “deposit then borrow” flow that assumes ordered delivery can become a money printer if messages arrive out of order, arrive twice, or arrive after a state change you did not bind into the message domain.

This is the exact place where IBC’s explicit ordered vs unordered channels, sequence tracking, and timeouts are useful as a design reference. The IBC spec treats timeouts as part of correctness, including channel-level behavior on ordered channels when a timeout occurs. That framing is worth copying even if you’re building on EVM.

4) Liveness failures quietly become safety failures

In 2026, we see this most in optimistic and “fast bridge” designs, and in systems that rely on off-chain services for execution. If relayers stall, if challengers can be censored, if dispute paths can be griefed into long-running states, you can end up with a system that remains technically “secure” but has failure handling that forces humans to take over.

That takeover path tends to expand admin power. If you have not designed it carefully, you’ve swapped one trust assumption for a worse one.

Principles for writing cross-chain code that survives reality

This section is where we’d spend our time in an audit review. These are the patterns we want to see, regardless of which messaging layer you picked.

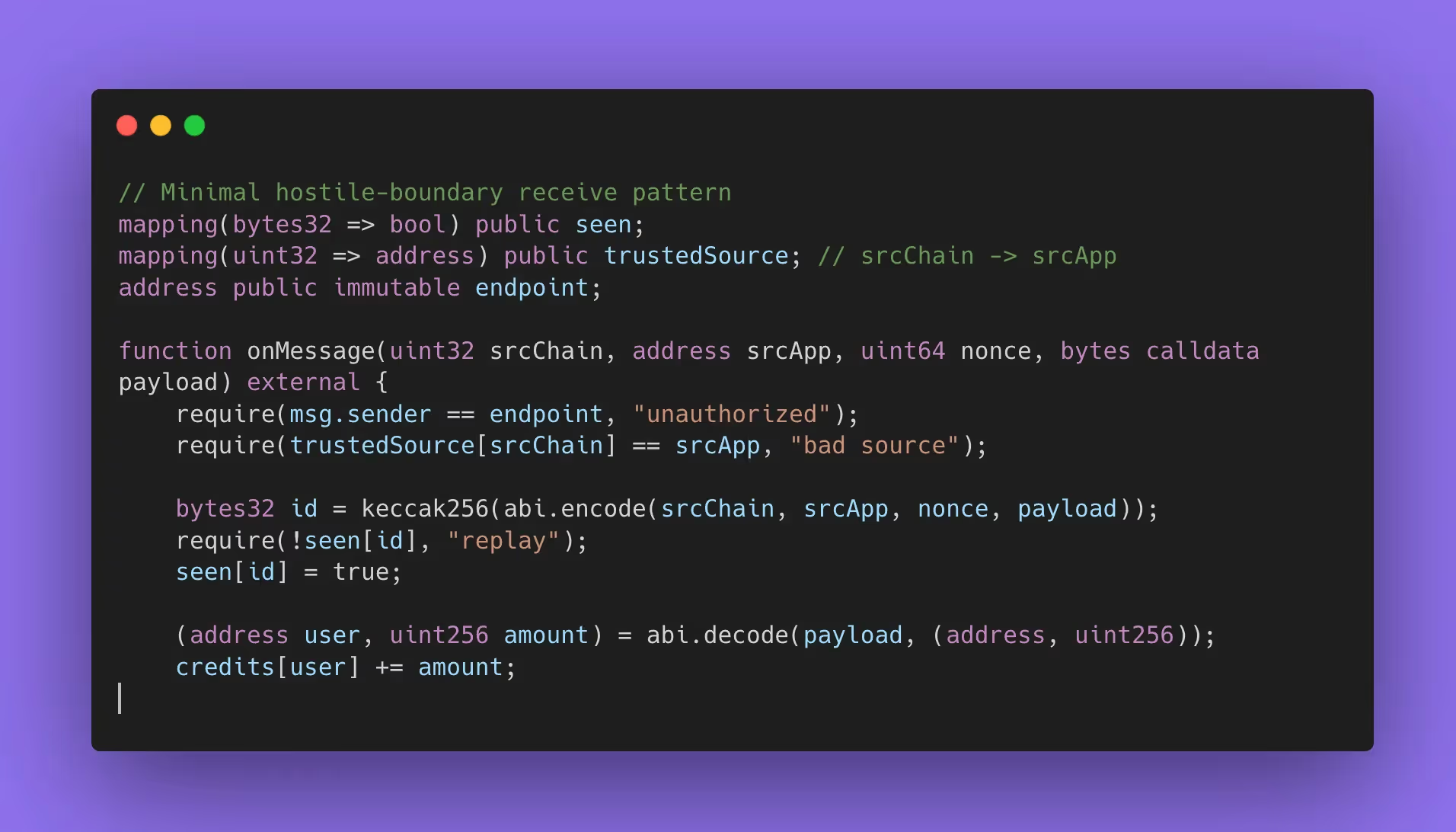

Treat inbound messages like hostile inputs

On the destination chain, an inbound payload is an external call shaped by another execution environment plus off-chain machinery. So the receive handler should behave like a hardened boundary: strict decoding, strict bounds checks, tight allowlists, and rejection before state mutation.

A common cross-chain pattern is “credit a user on chain B when they deposit on chain A.” The dangerous version trusts whatever payload shows up and updates balances immediately. The safe version treats the payload like hostile input: it only accepts calls from the bridge endpoint, only accepts messages from an allowlisted source app on a specific source chain, and only processes each message once.

If your handler decodes arbitrary bytes and then forwards calls based on payload contents, you’ve built a remote-control surface. That pattern is especially common in general message passing systems, where the selling point is “call any function on any chain.” Axelar’s GMP docs capture that power directly, and that is exactly why apps need to harden how they interpret payloads.

Make authentication explicit, then bind messages to a domain

Most cross-chain losses collapse into one sentence: the destination treated a claim as authorized without binding it to the exact domain where it was created.

Two habits show up in designs we trust.

First, domain separation. Bind the message to source chain id, source contract, destination chain id, destination contract, and a version or channel identifier. This is how you prevent replay across pathways and upgrades.

Second, commit/execute separation. Keep “verified and committed” separate from “executed,” so execution references an immutable commitment. LayerZero’s V2 docs and FAQ describe a flow where verification, commit, and execution are distinct steps, and lzReceive executes only after a message is committed on the destination endpoint. Their public code even flags that executor-provided extra data is untrusted and should be validated, which is exactly the mental posture you want at this boundary.

Design the receive path for duplicates, retries, and disorder

You will see duplicates. You will see retries. You will see messages delivered out of order in some transports. The safest receive paths are idempotent: a message can be processed at most once, or processing it twice is harmless.

If your application requires ordering, do not assume ordering. Enforce it with explicit sequencing and fail closed when sequencing breaks. Again, IBC is a clean reference because it makes ordering a protocol-level choice, and it specifies how sequences and acknowledgements behave.

What changed in 2026: economics, monitoring, and composability

Cross-chain security in 2026 is being shaped by usage patterns more than new cryptography.

Fast bridging and “execute immediately” UX pushes more pressure onto timing, ordering, and watcher incentives, which expands the economic threat model. Cross-chain MEV is now its own category: searchers can front-run messages between chains, sandwich liquidity operations, and manipulate price inputs that affect bridged asset valuation. In reviews, we separate “can forge a message” from “can profit by manipulating message timing,” because both can bankrupt you.

Monitoring is also moving from “nice to have” into the security budget. Real systems need watchers, independent verifiers, anomaly detection on message patterns, and reconciliation checks that alert when balances drift from expected accounting. This matters because many drains are fast, and the only way to stop the bleed is to detect early and halt.

Finally, composability turns bridge risk into systemic risk. When a lending market on chain A accepts collateral bridged from chain B, priced by feeds that incorporate chain C, the blast radius is not one contract. It’s a graph. Cross-chain security is no longer just “bridge correctness.” It’s about how bridged assets become primitives inside DeFi and how failures propagate.

Closing: cross-chain security is an operating posture

In our day-to-day work, the teams that do best are the ones that treat cross-chain as a full system: the verification model, the message boundary, the app state machine, the economic surface, and the incident playbook. They write down assumptions in plain language, they bind those assumptions into code, and they build monitoring that tells them when reality starts to diverge.

If you build cross-chain code in 2026, you are importing authority across domains. The job is to make that authority explicit, narrow, and survivable when something goes wrong.

Building cross-chain infrastructure? Sherlock's audit teams specialize in bridge security, messaging protocols, and multi-chain systems. Talk to us before you go to production.

FAQ - Cross-Chain Security in 2026

What are the main security risks in cross-chain bridges?

The main risks are message forgery, replay, ordering failures, and key or signer compromise. These risks exist because cross-chain systems grant authority based on external claims, not local execution. A single accepted message can mint assets, unlock collateral, or move funds across chains. When a trust assumption fails, losses tend to be immediate and total rather than incremental.

Why do cross-chain exploits usually lead to full protocol drains?

Because cross-chain systems concentrate authority into a narrow execution path. Once a forged or replayed message is accepted, it often bypasses normal user limits, rate controls, or multi-step flows. Unlike local bugs, which often affect one user at a time, cross-chain failures tend to trigger privileged logic that was designed for trusted system messages.

How do replay attacks work in cross-chain messaging systems?

Replay attacks occur when a valid message is accepted more than once or in more than one context. This happens when messages are not bound to a specific source chain, source contract, destination contract, and version. Even with valid signatures, a message can be replayed across routes, upgrades, or chains unless domain separation and one-time execution are enforced in state.

What is the safest way to handle cross-chain messages in smart contracts?

The safest approach is to treat inbound cross-chain messages as hostile inputs. Destination contracts should gate execution to a trusted transport, allowlist expected source domains, enforce replay protection, and separate message acceptance from execution. Execution should only occur after a message has been explicitly committed and should be safe against retries, duplication, and reordering.

Are light clients safer than multisig or oracle-based bridges?

Light-client designs shift trust from people and keys into verification logic, but they are not automatically safer. They depend on correct implementation of consensus rules, correct finality assumptions, and safe upgrade paths. Multisig or oracle-based systems fail differently, usually through key compromise or operational breakdown. The real difference is not the model itself, but whether its trust assumptions are explicit, enforced, and monitored.