How to Audit Your Own Smart Contract Before Hiring an Auditor (2026 Guide)

Learn how to audit your own smart contract before hiring an auditor. This 2026 guide from Sherlock covers scoping, threat modeling, testing, fixing issues, and preparing your codebase for a deeper external review.

.avif)

Teams often search for ways to review their own smart contracts before booking an audit, and the truth is that early self-auditing helps more than most people expect. When code reaches Sherlock after a first internal pass, we see fewer shallow issues, clearer intent, stronger test coverage, and a smoother path into deeper security work. That early effort shapes the entire audit process and gives external reviewers a clearer view of the parts that actually matter.

This guide lays out how to run that internal review step. It reflects what Sherlock has seen across hundreds of engagements: patterns that catch issues early, habits that tighten design choices, and simple practices that raise the quality of the code entering an audit. If your goal is to prepare your contracts, reduce friction during onboarding, and hand auditors something they can push hard on, this is the process we recommend.

Start With a Clear Intent for Your Self-Audit

Before looking at code, set the frame for what this internal review is supposed to accomplish. The goal isn’t to “replace” an external audit. It’s to remove obvious mistakes, surface assumptions you may have forgotten about, and tighten the structure of the system so an outside reviewer can focus on deeper attack paths. Teams that treat this step seriously enter audits with fewer blockers, fewer rewrites, and far more confidence in how their contracts behave under pressure. Sherlock sees the difference immediately during onboarding.

As you begin this pass, center the review around three anchors that guide every decision:

- What must always remain true?

Invariants for balances, permissions, supply, liquidity, or timing. - Who can influence the system?

Admins, oracles, multisigs, external protocols you rely on, and any address with special rights. - Where can things break under stress?

Areas with complex math, chained interactions, or state transitions that need closer attention.

These anchors turn a vague “self-audit” into a structured process. Once they’re written down, everything that follows (tests, fuzzing, tool output, manual review) has a clear target.

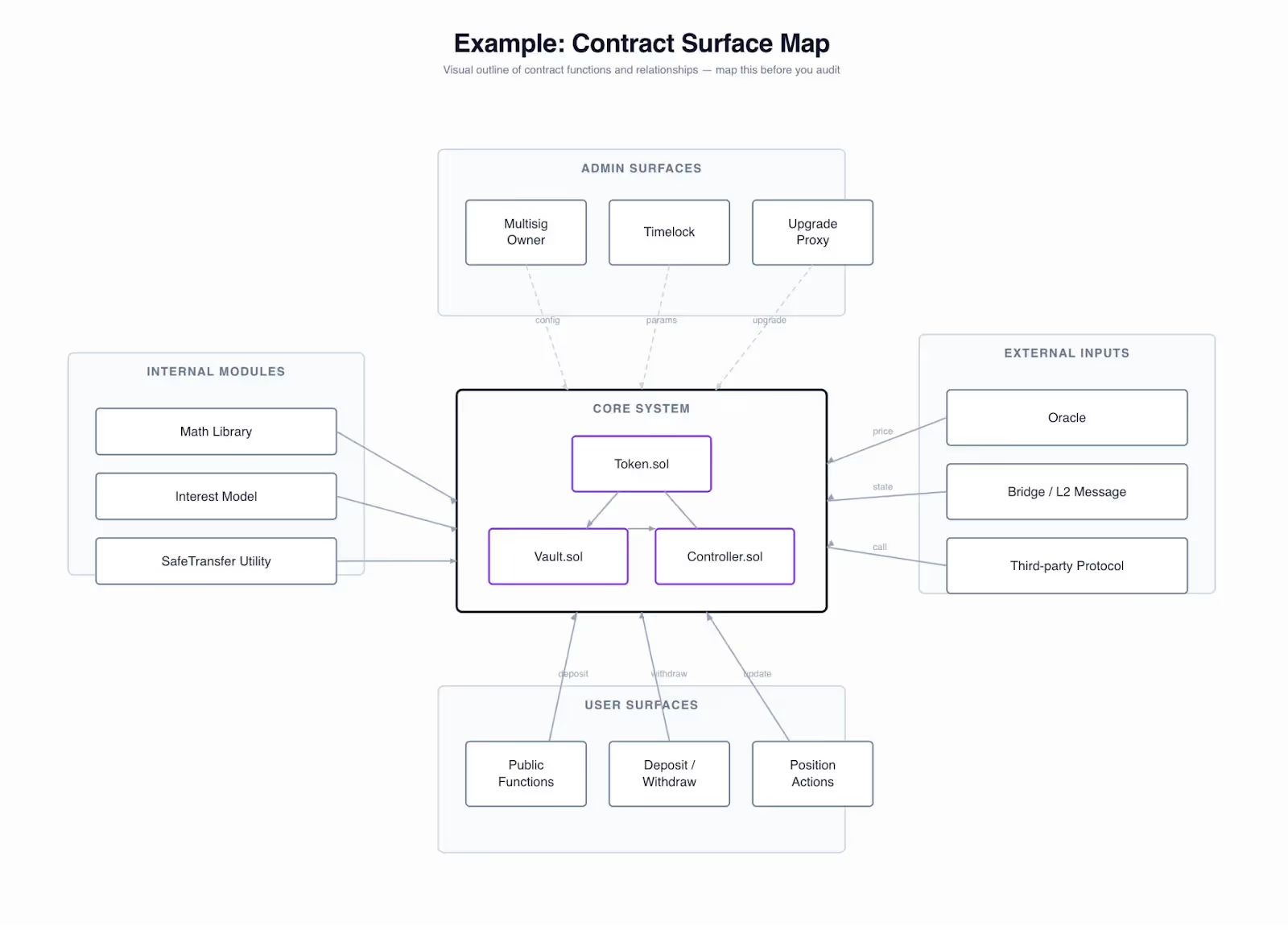

Map the Scope Before You Read a Single Line

A strong self-audit starts with a clear map of what’s actually in play. Contracts often accumulate helpers, experiments, unused modules, legacy patterns, and half-finished ideas over months of development. If you begin reviewing without untangling this, you lose time and miss context. Sherlock sees this frequently during onboarding: teams jump straight into security thinking while the project structure itself stays messy. The simplest first step is to group contracts by purpose, trace how they talk to each other, and list which ones are meant to touch user funds. This alone removes confusion and gives structure to everything that follows.

Once the architecture is outlined, build an index of every function that matters. Note which ones change state, which ones take external input, which ones call out to other protocols, and which ones carry admin authority. By the time an auditor looks at the system, they expect this clarity. Doing it yourself early creates a map of intentions and touchpoints so you can challenge your own assumptions. When your internal pass begins, you’re no longer wandering through code; you’re reviewing a defined system with known surfaces.

When Sherlock receives repos without this mapping, a noticeable chunk of early audit time goes into basic orientation; teams that hand over a clean scope often recover one to two full days of reviewer attention on deeper issues instead.

Work Through the Code With a Structured Attack Mindset

Once the scope is set, the actual review starts. The most productive internal passes come from treating the code the same way an attacker would: looking for places where assumptions slip, where state changes can be pushed out of order, or where outside actors can influence flows you thought were stable. Every high-quality self-audit Sherlock sees has one common trait: the team slows down and subjects each function to the same pressure they expect from production traffic, unexpected sequences, and hostile callers. This keeps the review grounded in how contracts behave under strain rather than how they were intended to behave on paper.

• Walk each state-changing function and confirm who can call it and why that access exists at all.

• Check every external call and imagine what happens if the callee misbehaves, reenters, or returns unusual values.

• Trace all arithmetic that touches user funds or system balances and ask where rounding or ordering can shift value in unintended ways.

• Identify assumptions about tokens, oracles, bridges, or modules you do not control and check how they behave under edge cases.

• Look for spots where a long chain of actions depends on one unchecked condition, especially initialization paths or upgrade flows.

The strongest internal reviews happen when teams treat every function as a potential attack surface rather than a feature they already trust.

Turn Your Assumptions Into Tests

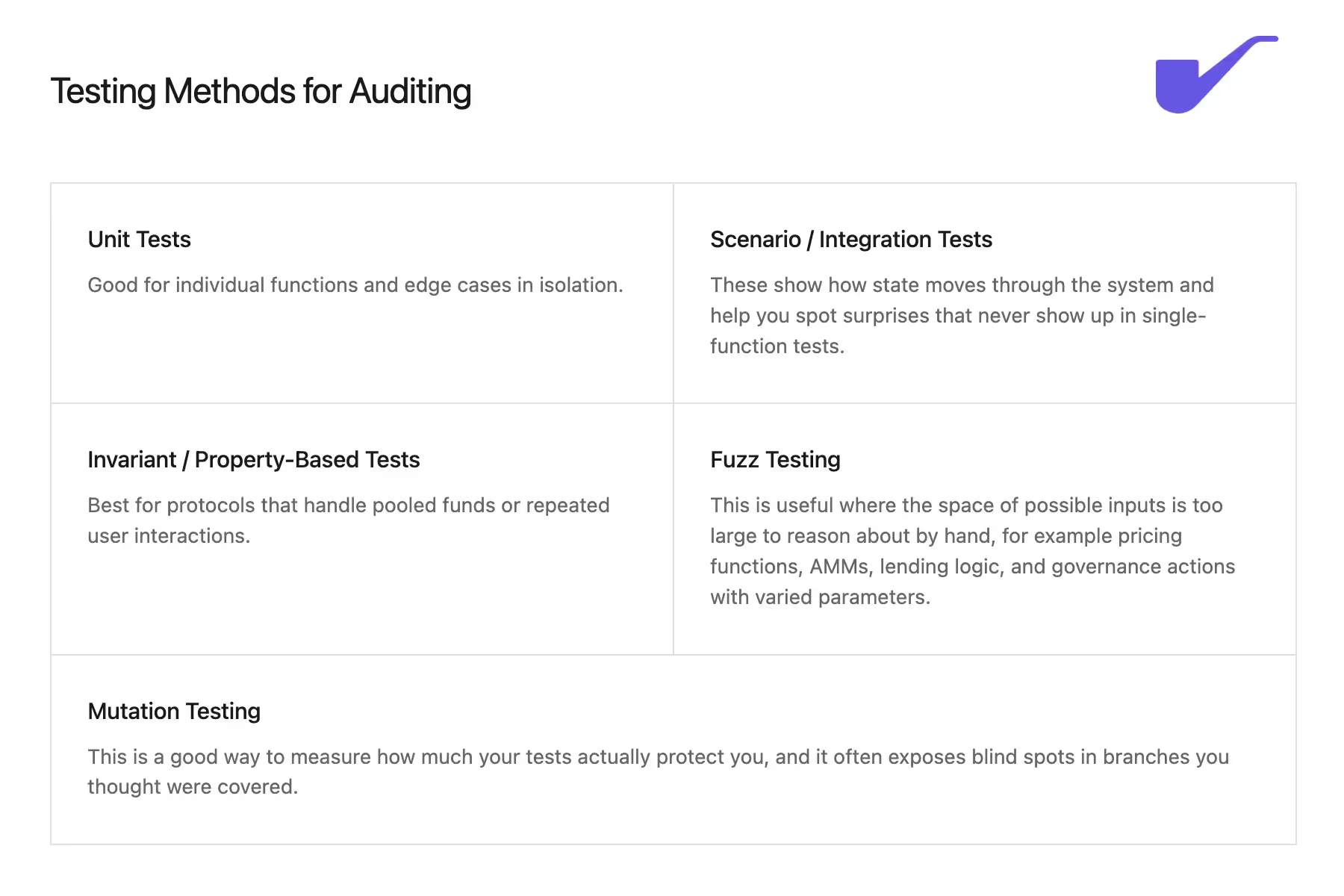

Once you know what should never break and which functions matter most, the next move is to encode that into tests. When Sherlock receives a codebase with strong tests, we see fewer questions about basic behavior and can focus on how the system might fail under stranger conditions. Your invariants from earlier - supply, permissions, liquidity, timing - should all show up inside a test suite that runs on every change. If you cannot express an assumption in a test, that is usually a sign the design is vague or the contract has too many hidden branches.

Start with simple unit tests that cover happy paths, then add scenario tests that chain several actions together and watch how state shifts across the system. For each important function, write at least one test that tries to break it: bad callers, bad inputs, wrong order of operations, and strange token behavior. Include revert checks wherever you expect the system to say “no”. Over time this suite becomes your internal safety net. When you later add fuzzing or more advanced tools, they build on top of a foundation that already guards against the most obvious mistakes.

If you find yourself explaining an assumption out loud more than once, turn it into a test. That habit alone catches a surprising number of bugs before an auditor ever sees the code.

What to Do With the Results

Once the tests are in place, treat every failure as a signal about how your system behaves rather than an annoyance to patch over. If a test breaks, trace the root cause and write down what assumption didn’t hold. If a scenario passes when you expected it to fail, ask whether the contract is allowing a state it shouldn’t. As this feedback accumulates, patterns emerge: fragile areas of code, unclear permission flows, arithmetic that shifts value in ways you didn’t anticipate, or paths that rely on too many conditions staying perfectly aligned. By the time you finish this cycle, your audit prep shifts from guesswork to a clear list of behaviors that need tightening before an external reviewer steps in.

Review Findings And Fix The Highest-Impact Issues First

Once you have tests, failing scenarios, and a set of suspicious functions, the work shifts from detection to repair. This is where self-audits either pay off or stall. The strongest teams Sherlock works with treat findings like a queue to be triaged, not a random pile of TODOs. They rank issues by how much damage a bug could cause, how easy it is to trigger, and how entangled the code around it has become. That order matters: if you clean up high-impact paths early, later changes become smaller, safer, and easier to reason about.

A simple way to approach this is:

- Start with anything that can lead to loss of funds, frozen funds, or permanent loss of control over the system.

- Next, address permission issues and upgrade paths that grant more power than intended or bypass checks you rely on.

- Then, clean up code that is hard to understand, hard to test, or tightly coupled to many other modules, even if the bug is not obvious yet.

- Finally, tidy low-impact edge cases, gas quirks, or cosmetic issues that do not change security properties but still cause confusion.

As you fix each item, update tests to reflect the intended behavior, re-run your suite, and keep short notes on what changed and why. Those notes often become part of the audit package and give outside reviewers a clear story of where you found weaknesses, how you addressed them, and which areas still deserve extra scrutiny.

Disclaimer: A Self-Audit Is Preparation, Not Proof

An internal review strengthens your codebase, reveals blind spots, and raises the overall quality of what you hand to an auditor. It also sharpens your own understanding of how the system behaves under pressure. But a self-audit is still a pass conducted by the same people who wrote the code, and that creates natural gaps in perspective. After thousands of hours reviewing contracts, Sherlock sees this pattern everywhere: teams catch far more than they think, yet still miss issues that sit just outside their mental model of how the system works.

Treat this process as preparation rather than certification. The purpose is to clear noise, tighten assumptions, remove avoidable risks, and give external reviewers more space to dig deeper. When this groundwork is in place, audits move faster, findings hit closer to the real attack surface, and teams walk away with far more actionable insight. That’s the outcome this guide is meant to support.

Once you're ready to enter the auditing phase, read our guide on how to choose the best auditor for your launch.

Closing Thoughts

A strong self-audit sets the tone for everything that follows. It sharpens your design, trims weak assumptions, and gives outside reviewers a cleaner foundation to work from. Teams that invest in this step consistently see smoother audits, clearer findings, and far more confidence in the code they ship. Treat it as part of the build process, not a separate chore. The more clarity you bring into an audit, the more value you get out of it.

If you want support through collaborative auditing, an audit contest, or development guidance through Sherlock AI, contact our team here

FAQ

How far should a self-audit go before contacting an auditor?

Aim to remove obvious issues, map the system clearly, and build a strong test suite. You don’t need to catch every subtle problem (that’s the auditor’s job) but the code should be stable, documented, and behaving as intended.

Do I need fuzzing or invariant tests for a self-audit?

If your protocol handles pooled funds, complex math, or multi-step flows, yes. These methods catch classes of bugs that unit tests never touch. Simpler contracts can get value from them too, but the priority depends on your design.

How do I know when an issue is serious enough to delay an audit?

If it can impact user funds, block withdrawals, break permissions, or undermine upgrades, fix it before onboarding. Auditors can work around cosmetic or low-impact quirks, but core safety problems should be addressed early.

Should I include known risks or unresolved questions in my audit package?

Yes. Listing open concerns gives auditors a clearer target and often leads to stronger findings. Hiding them slows everything down and forces reviewers to rediscover what you already suspected.

Can Sherlock review code that is still changing?

We can, but it slows the process and dilutes reviewer focus. The closer your code is to frozen—feature-complete, scoped, and tested—the more value you get from collaborative auditing, audit contests, or Sherlock AI-assisted development.

This guide reflects general practices and patterns. It is not legal advice or a substitute for a professional audit.

Sherlock is not responsible for how you apply these steps or for the security of unaudited code.