Stablecoin security audits in 2026: what teams verify before launch

What stablecoin teams need to verify for security before launch in 2026: mint and redemption logic, admin controls, oracle dependencies, vault accounting, and cross-chain supply integrity.

Executive Summary: If you’re auditing stablecoin code before launch, focus on the few places where value can be created, released, or mispriced. This is the fastest way to find the bugs that actually lead to supply leaks, broken redemptions, or peg stress.

- Map the value state machine: write the mint → move → redeem → settle flow, then prove each transition consumes a one-time check (cap, nonce, claim, burn) so nothing can be finalized twice.

- Enumerate every supply and payout path: trace every route that reaches _mint() or releases collateral (bridge/migration/admin hooks included) and force them through one shared boundary for caps, roles, and ordering.

- Stress-test dependencies and accounting: enforce oracle freshness + fail-closed behavior, attack vault/share math with rounding/donation edge cases, and test cross-chain replay/supply desync scenarios.

What an audit has to prove before a stablecoin ships in 2026

By 2026, stablecoins are operating under a new kind of scrutiny. Integrations run deeper, distribution is wider, and edge cases get punished fast. Over the last two years, Sherlock has worked alongside some of the most watched stablecoin teams in the space, from MakerDAO’s DAI lineage to Aave’s GHO and Ethena, plus credit and RWA-adjacent systems like Maple and m0.

What we've found is the teams that ship cleanly verify behavior end-to-end before launch: how supply is created, how redemption settles, and how every “one-time” check gets consumed under real conditions. This article walks through what auditors prove in 2026: mint paths and caps, redemption claim safety, oracle gating, liquidation call graphs, vault accounting, and cross-chain supply integrity.

"What stablecoin developers need to verify before launch: every supply-increasing entrypoint routes through one cap boundary; every redemption claim is single-use; state updates happen before external calls; oracle reads fail closed and enforce freshness; liquidation flows can’t reenter core accounting; vault share math can’t be gamed via rounding or donations; cross-chain messages can’t be replayed across domains."

Start with a state machine, then audit the transitions

Auditors who do this work well usually begin by rewriting the product into a simple state machine:

Issuance intent → backing verification → mint → movement → redemption intent → burn or lock → settlement → finalization.

Once that’s on paper, the audit becomes a set of questions about transitions. Can a user move from intent to finalization without consuming the right “one-time” proof? Can any actor finalize twice? Can any actor mint without passing through the same constraints as everyone else?

This is why stablecoin issues are so often “logic bugs” rather than obvious arithmetic mistakes. A system can have perfect math and still let value leak if a transition is missing a guardrail, a nonce, or a piece of state that must be consumed exactly once.

Minting is a role graph problem, not an admin key problem

In real stablecoin systems, “who can mint” is rarely a single address. It is a role graph: minter roles, operators, upgraders, pausers, blocklist roles, emergency guardians, and often external systems that can trigger minting flows (bridges, issuance routers, custody adapters).

Audits go deep on three things:

1) All mint paths, not the main one.

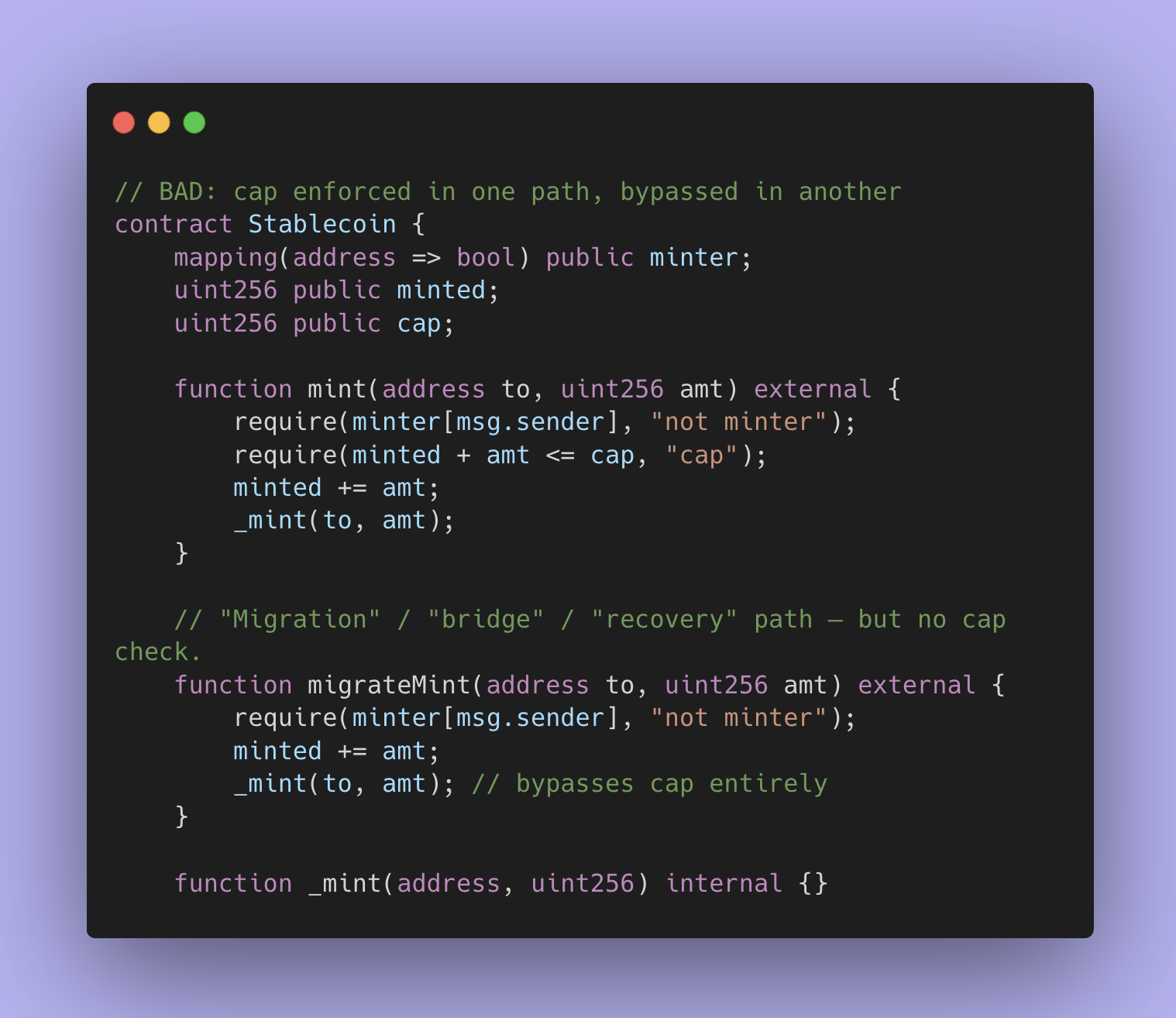

Teams often build a primary issuance route and then add special routes: migration mint, bridge mint, recovery mint, admin mint, upgrade mint. The most common catastrophic failure mode is an alternate mint path that bypasses caps or bypasses backing checks.

One of the easiest ways to break a stablecoin is not by hacking the primary mint function, but by finding an ‘alternate’ mint entrypoint that forgot to enforce the same caps or controls. Audits map every path that can increase supply and then confirm the cap check sits at the final mint boundary.

Here’s the pattern we look for:

2) Cap enforcement and where it binds.

A cap that exists in one function is not a cap if any other function can mint around it. Auditors map caps to every mint entrypoint, then test for bypass through upgrade hooks, role changes, or external integrations.

3) Signature systems and replay surfaces.

Stablecoins increasingly rely on permit and authorization flows for UX and integrations. That puts pressure on typed-data signatures, nonce consumption, and domain separation. If your signature scheme can be replayed across chains, forks, or contract versions, you can create approvals or authorizations the user never intended.

A lot of teams reach for standard libraries like OpenZeppelin for good reasons, but audits still verify the implementation details and how your custom authorization logic composes with the rest of the system.

Redemption is where stablecoins become real

Redemption is the part of the product markets care about most, and it’s the part that breaks under stress if you have a logic gap.

In audits, redemption failures almost always come from split-phase flows:

Request redemption now. Settle later. Finalize later.

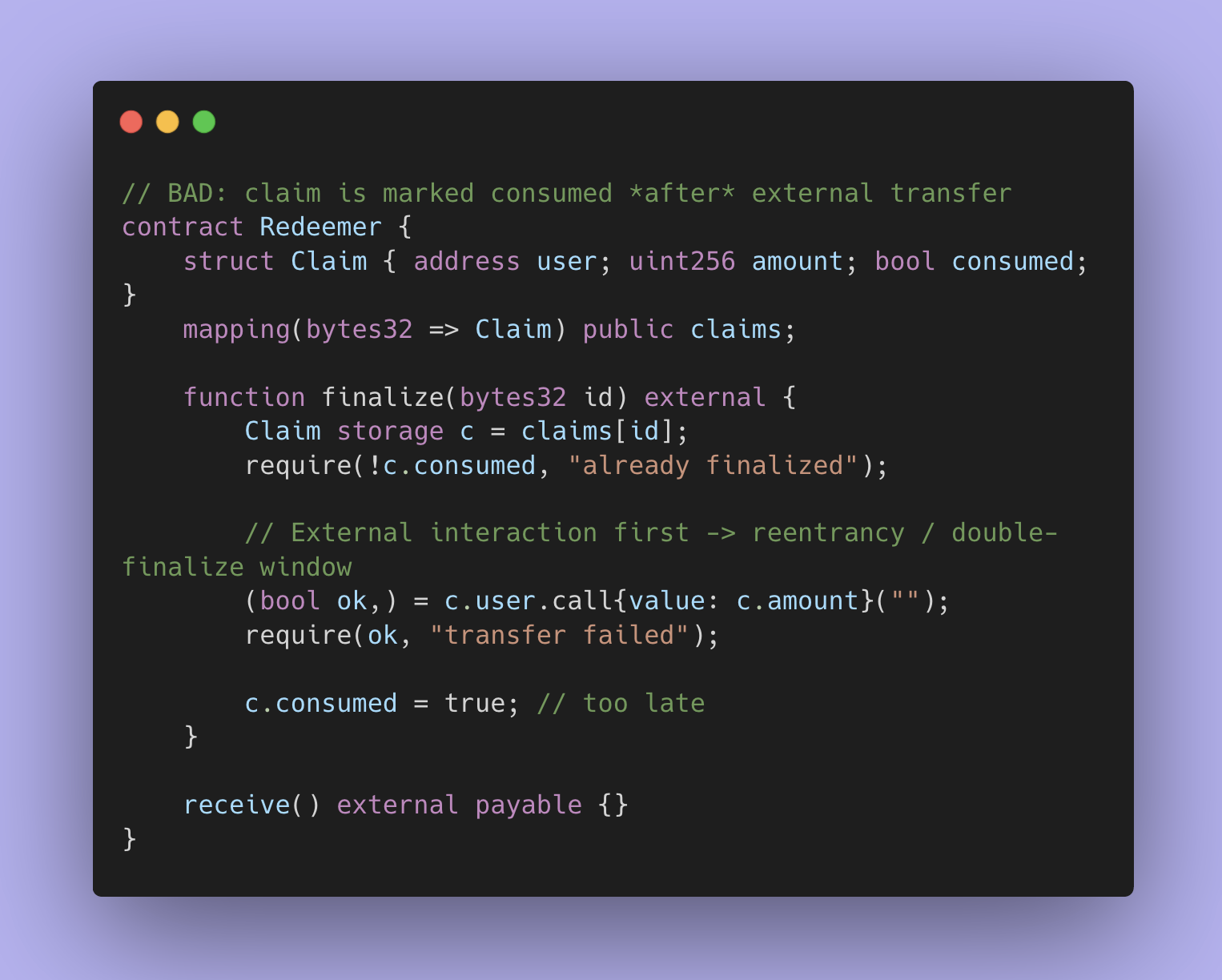

That design can be correct, but only if the system creates a “claim object” that is consumed exactly once, and only if state updates happen before external interactions that could reenter.

The core redemption invariant is: a claim can only be settled once. The failure mode is almost always ordering: transferring value out before the claim is marked as consumed, or leaving a window where finalize can be called twice through different routes. This is the minimal version of that bug.

When we pressure-test redemption, we try to break it in a few specific ways:

Can I finalize a claim twice by calling the finalize path from two different routes?

Can I reenter during settlement and cause the contract to pay out before it marks the claim as spent?

Can I cancel and re-request in a way that leaves my accounting in a favorable state?

Can I cause partial fills to under-burn supply or over-release collateral?

The cleanest stablecoin teams design redemption as a tight sequence with explicit state consumption, strict ordering, and crisp invariants that remain true even if an integration behaves unexpectedly.

Oracles are not data feeds, they are gatekeepers

If your stablecoin is collateralized, hybrid, yield-bearing, or interacts with credit systems, oracle inputs often gate the most sensitive decisions: mint limits, collateral ratios, liquidation triggers, redemption pricing, fee calculations, and solvency checks.

Audits map every place a price enters the system, then ask:

What happens if the feed is stale?

What happens if the feed is missing?

What happens if the feed can be nudged for one block at the exact moment a decision is made?

Stablecoin teams usually think of oracles as ‘price data,’ but auditors treat them as permission gates for mint limits, collateral ratios, and liquidation triggers. The most common bug class is accepting a price without checking freshness, bounds, or source assumptions. This is the minimal pattern that creates risk.

In 2026, oracle risk is also more compositional. A stablecoin might not “use an oracle” directly, but its collateral might. Its wrapper might. Its liquidation market might. Auditors track the full dependency chain, not just the contract you think is “the stablecoin.”

Liquidations and auctions hide surprising call graphs

For overcollateralized designs, the liquidation system is where the protocol self-corrects. It is also where complexity and external interactions stack up fast.

Auditors pay attention to liquidation modules because they often include:

External calls into bidder-provided contracts.

Flash-liquidity assumptions.

MEV exposure that changes what “fair price” means in practice.

State that can be manipulated between checks and effects.

Even when the stablecoin core is tight, liquidation logic can become a backdoor into value extraction if external calls can reenter sensitive surfaces or if auction accounting can be nudged in edge cases.

Vault wrappers turn stablecoin safety into accounting safety

Stablecoins today are frequently wrapped, staked, vaulted, bridged, or used as the unit of account inside a yield product. That shifts risk toward share pricing, rounding, fee accounting, and the correctness of totalAssets style accounting.

Audits go hard on questions like:

Can share price be manipulated by “donation” style moves that alter accounting without minting shares?

Can rounding behavior be gamed across deposit and redeem boundaries?

Does the wrapper assume the underlying is vanilla ERC-20 when the underlying has transfer fees, rebasing behavior, or nonstandard return values?

A yield wrapper that feels “simple” can still leak value if its accounting gets weird under small amounts, stressed conditions, or unusual integration flows.

Cross-chain stablecoins are supply systems with more ways to desync

Multi-chain is table stakes now. It also creates a larger blast radius.

From an audit standpoint, cross-chain stablecoins raise one core requirement: every cross-chain message that can create supply must be authenticated, non-replayable across domains, and bound to a single intent that cannot be reinterpreted by another contract.

Most cross-chain failures are not exotic cryptography breaks. They are business-logic breaks: replay, domain mismatch, authority leakage, or inconsistent supply tracking across chains after an incident.

What “ready to launch” looks like

By the end of a serious stablecoin audit, the goal is not “no findings.” The goal is that the team can answer, cleanly and concretely:

Exactly how minting can happen, and who can cause it.

Exactly how redemption settles, and why it cannot finalize twice.

Exactly where price assumptions enter decisions.

Exactly which external dependencies are trusted, and what the contracts do when those dependencies fail.

If you can state those truths and back them with tests and invariants, you’re in the small set of stablecoin teams that look like financial infrastructure before they even ship. That’s what 2026 demands.

Build or ship a stablecoin in 2026? Talk to Sherlock to audit your mint, redemption, and collateral system before it hits production. Contact us here.

Stablecoin security + auditing FAQ

1) What’s the single invariant auditors try to prove for a stablecoin?

That supply is never created or redeemed without the system paying its full “cost” exactly once. “Cost” could be backing settlement, collateral health, an authorization, a cap, or a burned claim. If any path lets you mint without paying cost, or redeem without consuming the claim, the system is broken.

2) What’s the fastest way a stablecoin gets “infinite minted” even when roles look fine?

A secondary entrypoint. Migration, bridge mint, recovery mint, upgrade mint, admin mint. One of them skips the cap or skips the backing check. Audits trace every path that reaches _mint() and force all of them through one shared boundary that enforces caps + authorization.

3) In split-phase redemption (request → settle → finalize), what are auditors trying to break?

Double-finalize. The classic failure is ordering: value is transferred out before the claim is marked consumed, leaving a window for reentrancy or two different finalize routes to pay the same claim. The fix is mechanical: claim consumed first, then any external transfer, and no alternate finalize paths that bypass the consume step.

4) How do auditors evaluate oracle risk for stablecoins beyond “is the feed correct”?

They map every decision that uses a price (mint limits, collateral ratios, liquidations, redemption pricing, fees), then test three conditions: stale data, missing data, and short-window manipulation. A feed can be “correct” and still be unsafe if your contract accepts old data or doesn’t fail closed when the feed goes dark.

5) What’s the most common vault / wrapper bug that causes value leakage around stablecoins?

Share pricing drift. totalAssets() or share conversion can be influenced in ways the wrapper didn’t expect (donations, rounding edges, underlying token quirks). Auditors try to create profit loops with tiny deposits, weird rounding, and “free” accounting moves that shift share price without minting shares.

6) If we’re cross-chain, what’s the main audit question that actually matters?

“Can any cross-chain message path create supply twice or on the wrong domain?” Auditors look for replay protection, domain separation, and a single intent per message. Most cross-chain failures are business-logic failures: replay, authority leakage, or supply desync during recovery flows.

7) What should a dev team hand an auditor on day one to avoid wasting a week?

A written state machine and a list of assumptions. Literally: “These are the mint paths, these are the redemption paths, these are the dependencies (oracle/bridge/custody/vault), and these are the invariants we believe must never be false.” If you can’t write that down, the audit turns into archaeology instead of verification.